Originally published 9/08/2014. Revised 5/3/2023.

Thanks to Karen Pryor's work, we now know the most effective way to teach animals new things. But what have we learned about the animals—and ourselves? How much more do we have to discover? As we celebrate Karen's 91st birthday this month, we revisit this classic interview featuring Karen's personal reflections on her 50-year career: the challenges, the triumphs, and her hopes for the future.

You were a budding scientist since early childhood. What sparked your interest in field biology?

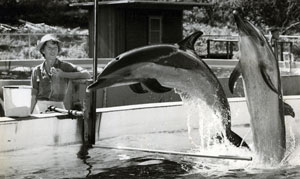

Karen and her dog Misha

Some people are fascinated by things when they first see them. I am one of those people. I was an only child so I had a lot of time by myself. We lived in a lot of places, but in the years from when I was 6 to when I was 12 I spent most of my summers in the country. I was in the woods, and on the pond, and out in the field. We had a little biome there, and it was absolutely filled with birds and fish and animals and plants to look at. I would spend my days out there collecting butterflies and catching minnows. My parents encouraged me. They were divorced, but they were both interested in the natural world. My mother was a good gardener and she would show me the early flowers in the spring and the little wildflowers from her childhood in the woods in Connecticut. And my father, in Miami, showed me fish and insects and things that interested him. So I am thankful that I had an opportunity to develop that curiosity.

In what ways have you used your love of field biology to make the world better for animals

It has certainly brought me back to observing carefully the emotional signals from the animal. I think that’s been left out of dog training for a long time, but also very much left out of laboratory research. They leave it out on purpose, and I kind of understand that. But if you’ve got it, why not use it?

The animal is throwing information at you all the time—maybe information that you can use. For me from the beginning, it’s been a blend of the field naturalist just watching and seeing what the animals are doing and trying to think why and what it means, and the trainer actually creating situations where emotions come bubbling up. The naturalist and the trainer have been mixed ever since I had the opportunity to train those first dolphins more than fifty years ago at Sea Life Park.

Let’s talk about those first dolphins. Clicker training is relatively new, but operant conditioning using event markers has been around for decades. How did marker-based training methods come about?

Training using a marker is based on the underlying operant conditioning principles that B.F. Skinner developed. General use of operant conditioning started in the marine mammal world. That’s where the first practical applications became widespread, and that’s where I learned it. That was in the early ’60s. A few psychologists knew about operant conditioning and understood it well enough to consult with the US Navy. The Navy was studying dolphins for military purposes in the early ’60s, very early on.

Karen and her first pupils preparing

for Sea Life Park's first dolphin shows

Two scientists were, in my opinion, responsible for the spread of the technology in the marine mammal community: Dr. William McLean, a scientist working with the US Navy, and Dr. Ken Norris, a marine mammal researcher and founding curator at Marineland of the Pacific, the country’s second oceanarium. Years before, Ken Norris, also a scientific advisor at Sea Life Park, studied a bottlenose dolphin for early research on sonar, hiring a psychology graduate student to train the dolphin. The student, a fan of Harvard psychologist B.F. Skinner, trained the dolphin using Skinner’s theories of operant conditioning. Norris asked the same student to write a manual on using operant conditioning to train dolphins for the Park, and the resulting manual was given to the Park’s new employees. Unfortunately, the manual was hard to understand. I got called in at the last minute because I had trained one dog and one pony, the conventional way. But I read the manuscript, and I just had to try it.

Learning to train both the dolphins and the trainers was fascinating, and writing the dolphin shows was fun! We opened Sea Life Park on time in October of 1963, with three species of dolphins and two different shows ready to go.

Marker-based training changed the way dolphins were trained forever, but why do you think it stayed isolated in the dolphin world for so long?

People don’t generalize very easily. So while we could explain how we train the dolphins in shows, people would say, “That’s so interesting, but of course I don’t have a dolphin.” We could use it with birds, we could use it with fish, whatever animal we came across at Sea Life Park, but even I did not think, “I should train my dogs that way.” At the time, I was still training my dogs the classical way, if I bothered to train them at all.

Even now it’s by no means generalized. By no means at all! Some people say that autistic children can’t generalize. My goodness, even Supreme Court judges can’t generalize. I would love to see that change, but it’s not going to happen in my lifetime.

So when did people finally realize that they could use this method to train their dogs? How did the clicker become the event marker of choice?

Shortly after I wrote Don’t Shoot the Dog, I began to share it with my neighbors, teaching them how to train their horses. I lived in the country then—you have a lot of time on your hands in the country. Then I gave a talk to the Humane Society in Seattle. Many people came to the talk, but two attendees called me afterward and said, “I need to know more about this. I want to do this.” One of them was an animal control officer named Gary Wilkes, and the other was Steve White, a canine cop. They both came out to my house various times, and they learned. We were using a whistle at that point, a dolphin trainer’s whistle, which I used to train my little dog to do some fun behaviors. The two men went back to their respective jobs and started using that training method, too, so they were very early adopters.

The ground-breaking book that

helped revolutionize dog training

I had been invited to give the President’s Invited Scholar’s Address at the Association for Behavior Analysis (ABA) Annual Meeting in San Francisco, which every year was given to an outsider with something to tell the behavior analyst group. In 1992, that was me. I said I would do it if I could also bring in a panel of trainers and show attendees what we do with their science. Our panel included Gary Wilkes as well as two other trainers: Ingrid, my head trainer from Hawaii at Sea Life Park, and a zoo trainer I knew, Gary Priest.

At the same time, I received an invitation to give a dog training seminar, and I didn’t want to do that single-handed. So I asked Wilkes if he would join me, because by now he had learned a good deal about the training and he was a good talker.

About a month or two before that was all going to happen, Gary Wilkes called me. He was living in Phoenix and said, “I just found these neat little clickers, and you can put your contact information on them, and wouldn’t this be a good thing instead of the whistle?” People don’t like having a whistle in their teeth all day. I said, “Sure, that would be a great idea.” So we got four hundred clickers with our contact information printed on them to give away at the meetings.

The four of us gave a panel discussion to the thousand-plus behavior analysts at the ABA meeting. It was very crowded. The panel discussion was overflowing—there were people standing against the walls and spilling out the door and into the hall. During the lunch break, on every floor psychologists were clicking—“clickety-clickety-clickety-click”—all over the hotel. But that didn’t mean that they had figured out what the clicker was for. They were playing with it, but they didn’t really adopt it. Amazing!

But the dog trainers did.

Two hundred trainers came to the dog training seminar. They all got free clickers. From then on, clickers started to be the way you trained dogs. That clicker became such a useful talisman. You know how easy it is... people pick it up, it makes a sound, the dogs goes, “what?” then you feed him, and now you’ve got a clicker dog. It’s so easy.

So that’s where the term “clicker training” started, and that’s where the infection began to spread. It went from, “It’s going to live forever in the marine mammal world, no one else is going to care” to spreading to the dog world, right there at that seminar. Animal behaviorist and veterinarian Ian Dunbar was at that seminar in May of 1992. Some people from Toledo also came to that seminar and invited us to give another one in their city. So it began to spread, by word of mouth at first.

How did marker-based training using the clicker spread into the dog world so quickly from that one small seminar? “Who let the dogs out?”

The person that clinched it was actually a math teacher, Kathleen Weaver. Kathleen began using marker-based training in her volunteer work for the K9 folks in her local police force. It worked so well that she began using it in her high school class. That success made a big impression on Kathleen; she was able to use this method to reach the teenagers who were lolling in the back, refusing to participate.

Kathleen started Click-L, the first clicker discussion list. She monitored and ran it, and in no time at all we had 400 people on the list. That list became the place where people started talking about clickers and learning to use them, and it quickly became the grandfather of all clicker lists. We had a big long running discussion going. That wouldn’t have happened without the internet. So it was that confluence in 1992 that shook clicker training loose, and you couldn’t put it back in the bottle after that!

Is there a difference between understanding how to use the clicker and really understanding how it works?

Yes, that’s two different mindsets. Some people are perfectly happy to use the clicker, have fun with it, get better at it, and do things with it. Other people want to know everything about how and why the clicker works to facilitate teaching and learning. Our Karen Pryor Academy (KPA) instructors are much more interested in what to do with the clicker based on the underneath rules. They want to learn that, and we want them to learn that, so they can teach people from the basis of understanding the principles, whereas the average person may be happy just to have the methods that come out of those principles. Methods can get twisted and misused easily, but if you understand the underlying principles you won’t have that problem.

I once watched a police horse training demonstration where a trainer shoved a giant target stick (it looked like a toilet plunger) in the horse’s face. Startled, of course, the horse threw his head up and backed away. The trainer knew the method: present the target, click for touching the target, then treat. But she was not thinking about the principles, such as “Start with a behavior the animal is already doing,” and “Build trust; don’t frighten the animal when you want it to learn.” At that demonstration, my friend Tim Sullivan, curator of behavioral husbandry at the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago, leaned over to me and said, “You can always tell when a trainer is coming from method instead of principle.” Boy, can you ever! Golden words. But methods are useful, and clicker methods are better than the old methods, I’ll tell you that.

Once it reached the dog world, it didn’t seem long before positive training applications appeared in other areas, such as zoos. What was the gateway?

Zoo animal care is one area where clicker training and positive reinforcement training have made a huge difference in improving the lives of animals. Zoo trainers think to themselves, “Here’s this thing I do with my dogs. I can use this with the elephants. I could use it with my giraffes.” Sometimes it’s spread that way.

Once the zoo world discovered positive training, it spread because it provided a way to take care of animals medically without dangerous, awful, or frightening procedures—such as either immobilizing the animal chemically or in a squeeze cage.

Karen delivering a grape to a

giraffe-necked antelope

In zoo care, many times you are dealing with a big and dangerous animal, like a tiger or a rhinoceros. It’s frightened and you’ve got to give it an injection. I once had a consulting job at a national zoo and they had a pair of rhinos there, mother and baby. The mother had tuberculosis, and they had to destroy her. Now if they could have called her over to give her a shot every blessed day, they could have cured her and she would have lived. For the keepers, the difference between losing an animal that they cherished and being able to take care of it, give it antibiotics, give it the care it needs, take the infected tooth out—all of the things you can now do with clicker training—that was very motivating! But at that time the national zoo staff had to kill the rhino, because they couldn’t even conceive of the fact that you could teach her to come over and give you her shoulder and take her medicine.

I think that the real catalyst for positive training in zoos were the marine mammal trainers who began coming into the zoos. The marine mammal trainers could train anything to do anything. So they were a source. Not in every zoo; there was resistance. There still is in 2014; sometimes I still hear a curator say, “Not with my animals, you don’t need to mess around with my animals.” There’s a lot of old tradition getting in the way.

But the infiltration just in the last 10 years, this century, has been dramatic, and it spreads faster every year. Now there’s the Animal Behavior Management Association (ABMA). Those members are all zookeepers, scientists, and curators, and that’s what they work on. Now I think to myself, “Oh good, I’m glad you guys picked it up!” It just took 50 years.

Are there any species of animals that can’t be trained?

It was one of B.F. Skinner’s students, Keller Breland, who said, “I can train any animal to do anything that it is physically and mentally capable of doing.” There are animals that are obviously very intelligent; we have to give credit to the great apes, the dolphins, and so on. But that’s not it exactly because if you are using this method of teaching them to find ways of making you click, it’s surprising how most of them find ways. The animals will communicate with you. They will look at you and ask, “Is this what you had in mind?” and then you click. It’s amazing how far down you can go with the game “Show me something new” if you are adept at setting up the criteria and bringing along the animals so that they can love the game and be ready to guess. That’s true of a guinea pig, that’s true of some fish, and that’s certainly true of a lot of birds.

I don’t know where the bottom line is to learning this way. I’ve given up trying to guess. Is it down there with the earthworms? I don’t know. It looks like certain molecules that are released in the brain when you get that click are in bacteria, too. What are they doing there? Helping some one-celled organism make a better day for itself? I don’t know where the bottom is. I’m not sure there is one.

Why do you think that some species learn faster or slower than others?

There are physical limitations. I used to talk about teaching the dolphins to do what the apes are doing with sign language. And the professors would object, saying, “But they don’t have hands.” But what if we used push buttons or some other symbols that they can use for words? That went right over the professors’ heads.

Yes, there’s kind of a bell curve of physical dexterity, and a distribution curve of willingness to do new things. A species that is afraid of new things, probably for very good reasons, is not necessarily going to be a fast learner. You are going to have to break through that fear, that avoidance of new things. They are conservative animals, and they will take longer to teach. Spotted dolphins are an example; they don’t like change.

Retention is more important to some species than others, like rabbits. The funny thing about rabbits is that they seem to forget. You teach a rabbit something and if he doesn’t need this information for two months, he’ll park it somewhere, and it doesn’t stay, whereas a little terrier will remember it for years.

Are you surprised by all the new findings in animal intelligence? How much more do we have to discover?

No, I’m not surprised because I’ve worked with so many species. When you see an animal’s eyes light up, when you see an animal that comes zooming out to do its clicker work, and that animal is an octopus, it’s a shellfish, you can eat it, and it’s all excited... I’m very impressed.

I’ve become very humble about animal intelligence. I think an animal’s ability to learn, think, and have feelings is more than we thought… much more than we thought. I wish the cognitive psychologists would use some of our tools instead of theirs, because our tools are much more efficient when trying to find out what animal can do. We just set them up and let them show us. They show us whether we want them to or not.

But it’s hard to take data that way. The way you take data in the lab can make it impossible for the animal to initiate anything. So we still have a lot of work to do on experimental design, I think, before we can discover how much more animals are capable of doing.

When did you realize that this technology would work with people?

I knew that from the beginning. I really did. Probably from the first week that I was applying this new stuff to the dolphins, I knew it would work with people. It’s fundamental; this is how we learn to do things.

When did others begin to make that realization?

One gymnast tagging another gymnast

for correct response.

Photo courtesy of TAGteach International

Again, this is a gateway that dogs have provided. Dogs have been a starter for a lot of different applications. They really have. A dentist once called me and said, “You know, I clicker trained my German shepherd dogs and stopped yanking them around on choke collars—and then I started looking at what I was still doing with my kids.” Once people learn a few principles and see that they work with dogs, some can make a jump from one situation to another.

Theresa McKeon would be one of those people who made that jump right away. She was a gymnastics coach who had bought a horse at an auction and was having a hard time training the horse. She learned about the clicker online, and began training the horse with a clicker. One day she looked at the clicker and said to herself, “You know, I could really use this in my day job,” and she began using the clicker with her students. Now we call this TAGteach, and Theresa has helped to adapt the technology in many other fields, including education, business management, medical training, professional sports, military, and more.

But it seems that people are still yelling at their kids, their employees. Are you surprised at how long it’s taken people to realize that there are better teaching methods?

Yes, I’m surprised at how slow it is. Theresa McKeon has been giving TAGteach seminars for a good 10 years and it has been very gradual development in the number of seminars offered—from 2 a year to 10 a year to 30 a year. Very gradual.

The challenge is deciding who needs this method of training, how to persuade them that they do need it, and then how to teach it to them so that it sticks. With people, we can use words to teach others. But it’s important not to use too many words, and not to use words that have any kind of negative implication. That knowledge comes slowly. For instance, when a teacher says to you, “Now watch me, I want you to do this,” it suggests that you are subordinate and the only reason to do it is because the teacher wants you to. Doing something to please the teacher doesn’t always work, particularly with teenagers. They don’t care what the teacher wants; they only do it because they have to please him/her or because they need good grades.

However, a teacher can say, “Let me show you, let me demonstrate.” That is a completely different framework. Normally people pair the instruction with the overlay of what the teacher wants and likes and thinks you ought to be doing. You’ve got to get rid of that so that students have success that they themselves have generated. “Oh, it worked!”

You’re going to want to keep that flowing. There’s some neuroscience backing up that reasoning, too. But it’s been difficult to find a place where it generalizes, a place where everyone who sees it says, “Oh good, I want that.” That’s what I’d like to see, and we haven’t seen that yet.

What are some examples of human applications where this conversion has been happening?

A fisherman training a chicken to knock down

a domino at Terry Ryan's Chicken Camp

One place where conversion has been happening is a fishing company in Alaska that got their boat workers trained. It’s been 5 or 6 years now and they still send everybody through the same program: training chickens at Terry Ryan’s Chicken Camp. That’s a good ice breaker. “If I can train a chicken, I can train this guy who doesn’t know how to paint the wall in a straight line.”

Children with learning disorders and autism, with special needs, that’s an area where the teachers themselves have begun to get interested and start using it. There are pockets around the country. The state of Arkansas has a special needs program training for TAGteaching. And there are other counties where school systems have bought into it, but it’s scattered.

You are transitioning your roles at Karen Pryor Clicker Training from a management role to research. Do you see this transition as going back to the naturalist roots that you developed as a child?

Absolutely. I’m finally getting a chance to play again. Oh, it’s wonderful. I have some questions. I get to go into the laboratories and ask those questions of the people that are doing that work.

I think that because of the company’s, Karen Pryor Clicker Training’s, success, positive reinforcement training has spread so much that the chance of it dying and disappearing again is far less likely to happen than if it had stayed in the marine mammal world. But I’m not done yet. I’ve got more work than I can possibly complete in my lifetime.

Speaking of literature, is there another book of your own in your future?

Karen's new book is set

to be released this fall

For many years I’ve written short monthly pieces called “Letter from Karen” for our subscribers at www.clickertraining.com. Now the company has compiled a book of the best of these essays, some about training, some about science, some about whatever was on my mind at the moment, from wonderful butterflies to a dreadful tea kettle. The format of those monthly letters allowed me to make a few jokes now and then and not be serious all the time. I think the results are quite a lot of fun.

My thanks to you, Julie, for making so many wonderful essay selections for the book. Our editor, Nini Bloch, did a great job organizing the letters into chapters. I love it that you tracked down the wonderful cover photo. It was taken by a rather famous photographer for a German magazine, and we were lucky to get permission to use it. The comments coming back from preview readers are very favorable.

Post new comment