Scents, in many scenarios

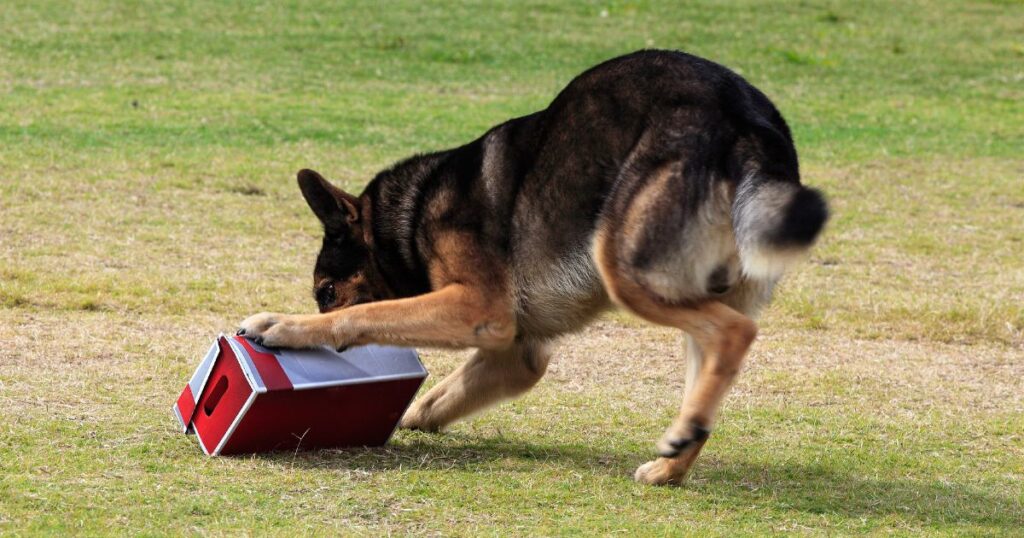

Scent-detection training has been receiving more attention in recent years. The use of dogs to alert on explosives has become increasingly critical in our ever-changing, politically charged world. New breakthroughs in medical-alert detection have created a demand for dogs that can assist patients with various medical conditions. Search-and-rescue dogs are still needed quite frequently; these dogs were perhaps some of the first dogs to use scent detection in critical ways. Although scent-detection training has been well-documented, many of the training techniques have not progressed much in the past few decades.

I have been helping with scent-detection projects for more than fifteen years, and have often been asked to solve recurring problems or challenges common in scent-detection programs. It is important to remember that dogs are already experts at the task of scent detection. Our role as trainers is to teach them which scent to find, when to find it, and what to do when they find it. In reality, the task of teaching a dog to alert on scent is pretty basic and straightforward; it is actually a minor part of the overall task. The most difficult aspects of scent-detection training fall into two categories: desensitization to working in the real world, and our inability to actually smell the odor ourselves.

Our noses are not as good

In scent detection, we have to teach our dogs to be reliable enough that we can trust them when they tell us that the odor is present. Equally important is trusting that when the dogs do not alert that means no odor is present. This confidence becomes critical in real-world scent detection. When a dog misses a find (fails to alert when odor is actually present), there can be serious consequences:

- For search and rescue, a missed find can mean a lost or trapped victim is not rescued and may die.

- In explosive detection, a missed find can result in a bomb being missed.

- With a medical alert, a missed find can leave a sick patient unaware and unprepared for a medical incident.

Both false alerts (indicating that odor is present when it is not) and missed finds are problematic. All serious scent-detection trainers take these challenges seriously.

Problems with typical scent-detection protocols

Most scent-detection dogs are trained to alert only when they find an odor. If an explosive-detection dog is asked to search an area, the dog will sit and stare at the source of odor when explosives are detected; if no odor is detected, the dog keeps searching and is not expected to offer any specific behavior. In many cases, once the search of an area is completed and the dog finds nothing, he is asked to move to a new area and keep searching. In real-world searches, explosives are rarely present, so the dog is asked to search area after area with absolutely no reinforcement. There is no correct response other than to keep working. No wonder the dog gets frustrated! Some trainers do give dogs a rest or offer some other type of reinforcement between search areas, but rarely does a dog receive his favorite reinforcer (usually a toy or a ball)—except when explosives are actually found.

Teaching an “all clear”

I have suggested that if teams trained an “all clear” alert, the dog would always have a correct behavioral response: one alert indicating that odor is present and a different alert (an “all clear”) to indicate that no odor is present. In this scenario, each time the dog is asked to search an area there is always a correct answer. While the addition of the “all clear” behavior seemed clear and helpful to me, it was so different from the existing norm that the idea was met with significant resistance. In an effort to convince trainers and organizations of the efficacy of the “all clear” signal, I suggested to several of the agencies I consult with that we conduct an in-depth review of the research literature, and conduct some experimental training trials with a few selected dogs.

If teams trained an “all clear” alert, the dog would always have a correct behavioral response.

A look at the science

I have worked on a number of research projects in my career that utilized a variety of investigative paradigms to help answer questions about how an animal or person perceives their world. Three of the paradigms that I thought would be useful for increasing the understanding of scent-detection training are “match-to-sample,” “two-choice,” and “go, no-go” paradigms. These paradigms are well-documented research procedures that ensure that the information we receive from studies is accurate and unbiased.

Matching to sample

“Match-to-sample” is a study technique that teaches the learner to perceive something (the sample), and then to find something else that matches the original sample. This procedure is used to test vision, smell, touch, hearing, taste, and almost any other sense that we want to investigate. It allows the investigator to determine the depth or complexity of an animal’s sensory abilities reliably.

When we teach a dog to find a specific odor, we are using the equivalent of a match-to-sample paradigm. The dog is taught to recognize a specific odor (explosives, narcotics, a person, low blood sugar, etc.), and alert us when a matching scent is found. By looking at matching-to-sample studies, I felt my law-enforcement clients could find the most reliable way of teaching scent detection so that the accuracy of the alerts was as high as possible.

Go, no-go paradigm

“Go, no-go” is a procedure that tests subjects’ perceptions by asking them to perform a specific behavior if they perceive whatever is being tested in the investigation. Conversely, if the subjects do not perceive anything, they are not expected to do anything in particular. This type of test is often used to evaluate a person’s hearing. The individual being tested wears headphones and is asked to raise either the right or left, hand depending which ear hears a sound when it is played. If the person does not hear a sound, no action is expected. This is a typical Go (raise your hand if you hear a sound), No-Go (do nothing if you don’t) type of study.

The biggest drawback to this procedure is that when the sound begins to get outside of the individual’s hearing range, and that person hears nothing for too long, many study participants begin to raise their hands randomly even though no sound is being played. Researchers have discovered that this is a typical test phenomenon. Presumably, the person does not want to get the wrong answer and begins guessing, or thinking s/he hears something, even though no sound is being played. In animal studies, the researchers discovered they had to work extra hard to make sure the animal was not “lying” in an effort to get more reinforcement. To me, this weakness of the “go, no-go” procedure resembled the challenges of typical scent-detection work, and could be a likely cause of false alerts.

Two-choice paradigm

In “two-choice” paradigms, the subject is asked to choose between two possible answers. This particular paradigm was invented to eliminate the uncertainty that is often created by the “go, no-go” paradigm. In many research settings, the two choices are set up as “yes” or “no” answers. In the redesigned hearing tests, the subjects are asked to touch a yes or no paddle to indicate if they hear a tone each time a light is illuminated in front of them. The light becomes the cue to touch a paddle and is, in effect, asking the question, “Do you hear a sound now?” The subjects wait for the light and then touch the appropriate paddle depending on whether or not they hear a tone. The subject always has an active option, a behavior to offer, no matter which answer is chosen. In these studies, the subject’s answers were more reliable and “honest” consistently.

The lack of accuracy in the results of “go, no-go” studies prompted me to suggest changing the approach to explosive-detection training. Give the dogs a yes (I smell odor) and a no (all clear, no odor present) behavior so that they always have a correct answer available to them in every search area.

Improved reliability

In the testing that we have done with more than thirty dogs in several scent-detection contexts, teaching an odor-alert behavior combined with an “all clear” behavior has been remarkably successful at reducing both false alerts and missed finds. (Anecdotally, it has also seemed to increase the dog’s enthusiasm for the searching and alerting tasks.)

The results have been quantifiable in real-world explosive-detection trials, with success rates averaging above 95% consistently.

The results have been quantifiable in real-world explosive-detection trials, with success rates averaging above 95% consistently. Previous data for real-world detection in some organizations was barely averaging 80%. Data will be presented in upcoming publications; I will write about the studies and results as they are available. But I am hopeful that those looking at scent detection in any context will consider the data that exists in the research community about the various research paradigms. This information is not new, and it gives clear evidence that there are techniques available to us as trainers that are well-documented and successful, and that might be useful in some of the new training applications that we develop for our animals.

Medical-alert detection

Working with medical-alert dogs is a slightly different situation. Unlike an explosive-detection dog that is cued to search an area and report, most medical-alert dogs are not cued when to alert. The medical-alert dog is expected to alert at any and all times—whenever the dog detects the odor she has been trained to find (i.e., low blood sugar for a diabetic-alert dogs). A medical-alert dog must be on the lookout for the desired odor all the time, alerting even when not cued to do so specifically. This requirement would make the “go, no-go” paradigm seem like the preferred approach in training medical alerts. However, some of the early work that has been done by various organizations indicates that using a “two-choice” paradigm during the early stages of the training sets the dog up for greater success.

Throughout her working career, the dog alerts whenever she detects the desired odor without being cued, in effect operating within a “go, no-go” paradigm. But, from time to time, the trainer can still ask if odor is present, which allows the dog to maintain the yes/no response as well—and keep her motivation and accuracy high.

Training medical-alert dogs is still new and developing work in many organizations. As we begin to share information on successful techniques, all of us who work with scent detection will become better informed. Ultimately, the animals will benefit from this shared learning and progress, as will any humans the dogs’ scent-detection skills can help.

Keep studying, learning, and sharing

I hope trainers will keep an open mind, and look at options and alternatives that will continue to improve the techniques we use to train scent-detection behaviors.

I will continue to write about the work I am doing in scent-detection circles, and keep abreast of the work being done by others. My goal is to stimulate some thought about future exploration for people working in similar fields. I encourage all trainers who work on scent-detection projects to share their experiences, successes, and failures. I hope trainers will keep an open mind and look at options and alternatives that will continue to improve the techniques we use to train scent-detection behaviors. We should always set up our animals for success: make the goals clear, and learning will be fun for the animals. Reliability will increase as well. Ultimately, in many of the contexts where scent-detection work is being used, the animals will be happier and lives will be saved—a win for all involved!

Note: This article was originally published on 11/25/2015 and last reviewed on 04/08/2025. We regularly review our content to ensure that the principles and techniques remain valuable and relevant. However, best practices continue to evolve. If you notice anything that may need updating, please feel free to contact us at editor@clickertraining.com.