What was the first animal you remember training?

I grew up on a ranch where my uncle kept cattle dogs used for herding and a few pet dogs. As a kid, I interacted and played with the dogs, without thinking much about training them, although they were in fact well-trained animals. I didn't become conscious of real training until I was 10 or 11, when we got a new dog and I needed to get him to sit and lay down and all that. I still didn't think much about training, but knew that I loved being around a dog.

When I was 15, I started volunteering at the Institute for the Blind, working with guide dogs. Then the idea of training as a formal activity became huge for me. I realized I had been around training all my life, as my uncle on the ranch was a pretty good animal trainer, although he never could have explained what he was doing. I spent three years working at the Institute for the Blind, and by the time I went to college, training guide dogs had become my passion.

How did your career begin, and when were you introduced to operant conditioning?

I first heard the term "operant conditioning" in college where I majored (at first) in psychology and animal behavior. It never came up during my years with the guide dogs, although operant conditioning was clearly being used by those trainers. The pieces of the puzzle, however, didn't come together for quite a few more years after that.

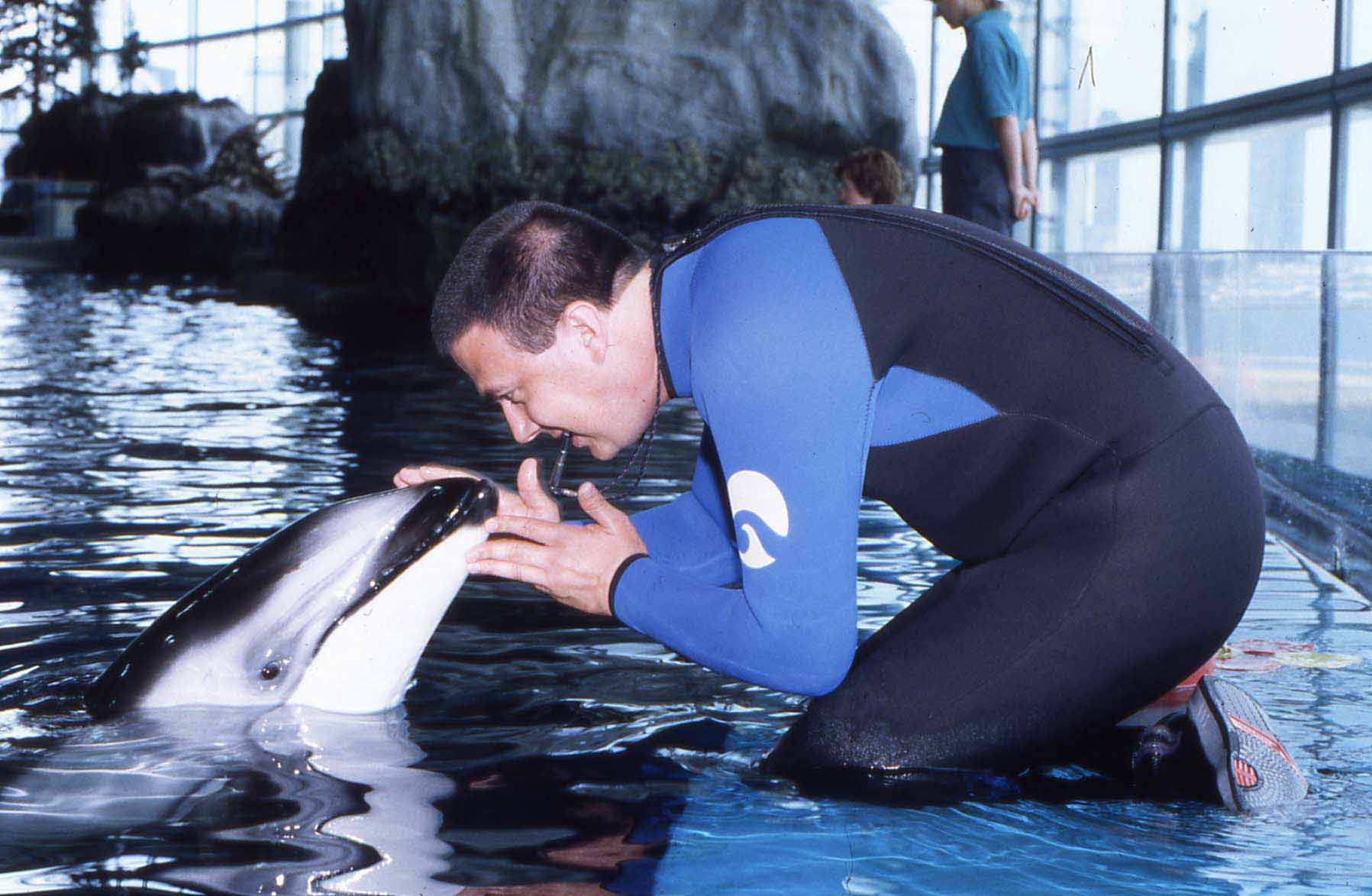

In my senior year, I took a summer position at MarineWorld of Texas in the education department, helping to narrate shows. While I had never dreamed of being a dolphin trainer, I found myself spending a lot of time hanging out with the trainers. What I had learned in my college behavior classes began to make sense as I watched them work. At the end of the summer, I was offered an entry-level trainer position. The position, however, required a degree in biology, whereas I was just completing a degree in psychology and animal behavior. So, in my last year of college, I switched my major to biology and started all over again so that I could get a job as a dolphin trainer.

As a new trainer, I began learning from experienced trainers who used both negative and positive reinforcement. My first assignment was to take care of the young animals that were going to be shipped to other locations. They didn't need any training; we just needed to keep them healthy. I was given permission to work with them, however, and so had the opportunity to train, on my own and with total independence, 36 dolphins from scratch. In the process, I realized I was never using punishers (which is difficult with dolphins in any case), and I was getting results. When I was well into my career, I read Karen Pryor's Lads Before the Wind and Don't Shoot the Dog, and finally all the pieces of the puzzle came together.

Over the years, you've trained a lot of people to be trainers. In your experience, does operant conditioning and positive reinforcement training—clicker training—require a fundamental shift in how most people approach training?

I've found that a trainer's receptivity to positive reinforcement training depends on what they've been exposed to in the past. Traditional training is very intuitive for humans because we live in a correction-based world. We grow up with our parents telling us "no," "stop," and "wrong," so it comes naturally to us. Even trainers who believe that positive reinforcement is the right way may use a lot of corrections and punishers without being aware of it. New trainers who have never been exposed to traditional training, or any sort of training, have the easiest time learning this method; it makes sense to them. Those who have been exposed to traditional training, and have had the feeling all along that something wasn't right, shift easily to operant conditioning. Those trainers, however, who have had some success with traditional training, who have been reinforced by that success, have a more difficult time shifting over. For you can have success with correction-based training, of course, but you will also have discomfort with abusive techniques.

One of the things I love about creating my own training program at the Shedd Aquarium is that we simply don't have a way of telling our animals "no." Once we have the ability to say no, it's too hard not to say it; even the most skilled trainers find it slipping it out of our mouths.

How do you recognize a potential new and talented trainer for your program?

So many kids dream of being a dolphin trainer. I had a passion for animals, but it never occurred to me to become a dolphin trainer. So, I look for more than an interest in dolphins. There are two sets of qualifications we look for in applicants: the tangible set on their resumes, and a second set that includes passion, commitment, responsibility, and maturity. The Shedd Aquarium volunteer and intern program allows me to evaluate that second set of qualifications in potential trainers before putting them on our payroll.

Where do people most frequently get hung up in their education as trainers? What have you found that helps people get over the next hurdle?

People get stuck in different places with different species. That's why I'm so pleased to have the opportunity to work with dog owners at ClickerExpos. At Shedd, with a large staff and large group of animals, we're extremely regimented in how we teach our trainers so they don't go off in wrong directions. We don't give them a chance to make mistakes. By the time we cut the chains and allow them independence in the training process, they're senior trainers. Flying free, they do get hung up, but they know how to work their way out of a training error. It's like raising children; at some point they're on their own, and you hope you've given them a solid foundation so that they make the right decisions. Dolphin trainers aren't allowed to get hung up for quite a while, and when they finally are allowed to make a mistake, they know how to fix it.

With one person and one dog, however, it's different. Dog owners are not with their animals all the time. A dog owner can't control every interaction 24 hours a day, yet every interaction is a potential reinforcer. (When we recognize that every interaction has reinforcement value, we realize that we're shaping behavior all the time.) A dog can't wait three to four years for its owner to gain training skills, so a lot of mistakes are going to be made along the way. So dog owners often get hung up right from the beginning, learn from their mistake, and move on. The second hang up I see in new trainers and dog owners is when there's a problem and they feel the urge to use a punisher. It's an instinctive response, and we want solutions fast. Deciding to control that urge is the first step in becoming a skilled trainer.

Your ClickerExpo course on "Developing Your Own Training Plan" is about organizing and using the information that you've learned. Why did you choose that subject?

So often, you go to a conference, and by the end, everyone is excited to try new things. Then we go home, and can't apply our new learning. The result is frustration and a lack of real progress. You often see this pattern in zoos and in the dog-training world, when some magical training approach works so well for a few trainers, but not for others. Usually the problem is that people copy a method without understanding the theory behind it. In the zoos, working with exotic animals, trainers can get hurt doing this. At home, dog owners tend to revert to saying "That trainer had a special dog; my dog is different."

Over time, I've developed a couple of steps I find helpful in putting new learning to real use. I realized what was happening was that people were not able to differentiate when something was out of their skill level or out of their animals' skill level. When adopting new training methods, a handler needs to ask, "Am I ready? Is my animal ready? Does this animal need more of a foundation before attempting this technique?" We need to realize when we are beginning trainers and when our animals are beginning learners.

My ClickerExpo seminar, therefore, will cover how to determine whether you are a beginner, intermediate, or advanced trainer, what the required learning is, and what the task skill level is. It will help trainers identify whether this is a new task to be learned or a problem behavior to be resolved. We'll talk about how to envision an end result and develop a training plan backward so that you can see the skills your animal needs before attempting that end behavior. You'll learn how to evaluate your skills to see where you're lacking. I believe that trainers need to realize that they can figure out how to fix something by looking at all the variables. They can figure it out themselves if they have a template for what do to. Then they can be creative, and look for ways to eliminate punishers and add reinforcers, and develop a shaping plan themselves.

Let's talk about modifier cues, the subject of another seminar you are giving at Expo.

Modifier cues are an advanced concept. They require an animal that is into the training game and understands the game. This is concept training. Clicker training is so precise that in a way concept training, i.e., generalization, is counterintuitive for both trainer and animal. However, once you can get an animal to understand a couple of concepts, to understand the idea of a concept, you can move forward very fast. Karen's game, "86 Things to do with a Box" is a good beginning way of looking at concept training. With modifier cues, we are specifying an idea, and then generalizing it. You can get started by training one concept first: take three identical objects and teach retrieve or touch one, such as the left object only. Once they have it, immediately begin teaching the one on the right. They're not trained simultaneously, but in conjunction.

I was introduced to the idea of concept training and modifier cues working with guide dogs. These animals need to understand, for example, the differences between spaces in which a dog can fit versus spaces in which a person can fit. The dogs learn to look at spaces and generalize their knowledge. When I saw that, I became really fascinated with how much you could teach a dog and how broad their understanding could be. Later, with marine mammals, teaching "left," "middle," "right object," and then teaching search and rescue dogs to perform out in the field without their handler, I began seeing a pattern emerge: Once an animal had understood at least two concepts, then concept training became straightforward. At Expo, I'll show a video of a beluga whale and of search and rescue dogs learning concepts and their modifier cues.

Is there a limit to what can be taught an animal through positive reinforcement and operant conditioning?

There probably is, but I haven't seen it yet. I'm constantly amazed at what an animal can learn, and how reliable they can be. I'm not sure we've even begun to scratch the surface of what their potential is yet. We're limited only by our imagination and our own skill set.

What is your next challenge? Is there a behavior or animal you would like to train, but haven't quite figured out how to do it yet?

I'm challenged all the time in my work. I've been so busy that I haven't been able to think up a behavior that I haven't been able to try yet. The big challenge on the horizon is a certification process for trainers. I'd like to bring the knowledge level of trainers up to a certain level so that everyone is practicing it in a certain way that is going to benefit the animals in the long run.

Post new comment